More than you might think. Sociality means group living. We form and maintain groups because all the individuals involved gain genetically. Are you a queen, drone, or worker bee? Has your hive shaped your role in it? In this article, we’ll turn our attention to eusociality—a sociobiological theory applied to ants, bees, and humans (to name a few).

Why examine Eusociality?

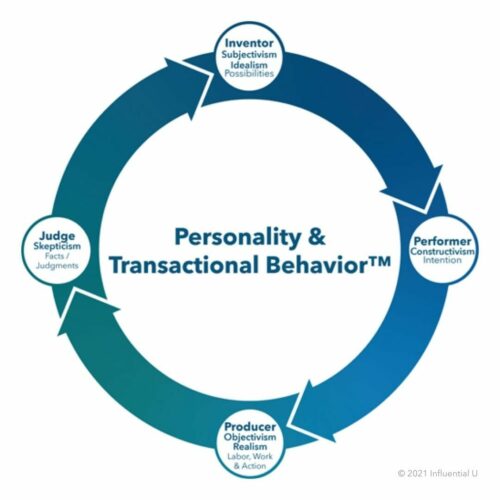

It validates our model of Personality and Transactional Behavior™

Influential U has gathered and studied over 220 personality models, most of which have their basis in a four-quadrant model. The earliest record of this was written in 400BC by Hippocrates.

Personality and Transactional Behavior is foundational to transactional competence. Within the teams or groups we occupy, each of the four personalities approaches exchanges according to their worldview or role. Each personality has a different job to do, and each role is necessary for the collective group to thrive. This is strikingly equivalent to an ant colony or beehive. For example, an ant colony includes a Queen (reproduce), Drones (mate), Workers (hunt/protect), and Alates (establish new colonies). While born genetically similar, environmental triggers evoke genetic switches to produce the perfect balance of the required roles. Each role allows the collective group to thrive. No one role has supremacy.

An incredible parallel

Queen (reproduce), Drones (mate), Workers (hunt/protect), and Alates (establish new colonies)

Inventor (future), Performer (relationship), Producer (doer), and Judge (protect)

We’ll expand on this similarity with bits of an article titled “The evolution of eusociality” [1] by Marin A. Nowak, Corina E. Tarnita, and Edward O. Wilson.[2]

This article and many cited within, “point to the parallels with the scenarios of [human] eusocial evolution … and they are, we believe, well worth examining.”[3]

Below are super-dense quotes, but we’ll use simple language, in bullet form.

Eusociality in Ants, Bees, and Humans

Eusociality, in which some individuals reduce their own lifetime reproductive potential to raise the offspring of others, underlies the most advanced forms of social organization and the ecologically dominant role of social insects and humans. For the past four decades, kin selection theory, based on the concept of inclusive fitness, has been the major theoretical attempt to explain the evolution of eusociality. Here we show the limitations of this approach.[4]

- Eusocial (simplified) means the group shares a role in raising the young in a durable nest and divides the chores.

- There are advanced forms of social organization, mostly seen in social insects (ants and bees) and humans.

- Inclusive fitness is a theory suggesting an organism’s (individual) genetic success is derived from cooperation and altruistic behavior.

- Inclusive fitness falls short to explain ants, bees, and humans, for example.

- So, eusociality explains it.

Selfless Behavior doesn’t fit the selfish gene model

For most of the past half century, much of sociobiological theory has focused on the phenomenon called eusociality, where adult members are divided into reproductive and (partially) nonreproductive castes and the latter care for the young. How can genetically prescribed selfless behavior arise by natural selection, which is seemingly its antithesis? This problem has vexed biologists since Darwin, who in The Origin of Species declared the paradox—in particular displayed by ants—to be the most important challenge to his theory.[5]

- Selfless behavior doesn’t fit the selfish gene model.

- Said another way, we only want our own genes to proliferate. But that isn’t how we (or ants or bees) act.

- Hence the theory of eusociality.

Eusocial means clear-cut roles

Modern students of collateral altruism have followed Darwin in continuing to focus on ants, honeybees, and other eusocial insects, because the colonies of most of their species are divided unambiguously into different castes. Moreover, eusociality is not a marginal phenomenon in the living world. The biomass of ants alone composes more than half that of all insects and exceeds that of all terrestrial nonhuman vertebrates combined. Humans, which can be loosely characterized as eusocial, are dominant among the land vertebrates. The “superorganisms” emerging from eusociality are often bizarre in their constitution, and represent a distinct level of biological organization. [6]

- Eusocial critters divide into clear-cut roles.

- Eusociality isn’t trivial. These critters (human included) form massively abundant superorganisms.

- This is an advanced level of cooperation and organization.

Shaped by transactions and the environment

The full theory of eusocial evolution consists of a series of stages:

The formation of groups. The occurrence of a minimum and necessary combination of preadaptive traits, causing the groups to be tightly formed. In animals at least, the combination includes a valuable and defensible nest. The appearance of mutations that prescribe the persistence of the group, most likely by the silencing of dispersal behavior. Evidently, a durable nest remains a key element in maintaining the prevalence. Primitive eusociality may emerge immediately due to springloaded preadaptations. Emergent traits caused by the interaction of group members are shaped through natural selection by environmental forces. Multilevel selection drives changes in the colony life cycle and social structures, often to elaborate extremes.[7]

- Eusocial behavior develops in steps.

- These steps include forming groups, building a durable nest, and turning on and off the genes that make the group persist.

- Clear-cut roles are shaped by transactions with the group and environmental forces.

Eusociality validates Personality and Transactional Behavior

Sociality is one of fifteen Conditions of Life™. It is defined as functioning among others. As influential professionals, our chief concern is our fitness and ability to function well amongst other people: to get along, play well together, and cooperate. Sociality means “group living.” We characterize this condition as the formulation of any general theory of social behavior that begins with describing the selective forces causing and maintaining group living. In general, groups form and persist because all of the individuals involved somehow gain genetically.

One of the best ways to explore sociality is to understand it from a scientific view. In the book, The Social Conquest of Earth (2012), author E.O. Wilson produces a deep understanding of the origins of the human condition.

Why does this matter?

Teamwork isn’t easy because people are people. We each see the world from different points of view. Each view can sometimes work as a superpower—or paralyze like kryptonite.

Could we deploy our differences in our favor? Could we instead use our differences to remove the friction or dysfunction from our everyday exchanges—including those with our target market? Transactional Competence introduces a proven cultural framework that can scale.

This framework utilizes the inherent clear-cut roles nature gave us.

In most meetings across the globe, a prominent wasteful dysfunction transpires. Get a group of people together and a familiar pattern begins: One or more are tapping their fingers wanting to DO something. A few offer disruptive new ideas that are quickly shot down by others demanding the evidence for it to work. All the while, it seems some merely want to share, connect, and relate. From a small start-up to the United Nations; we can’t seem to get things done. Why? (think of the ants).

We don’t know that each role matters.

We don’t know that each role allows the collective group to thrive.

We don’t know that no role has supremacy.

We don’t know what transaction we’re building.

Teams reimagined

Imagine a meeting where, rather than ego, charisma, or complaint running the show, we could merely ascertain where we are in the transaction (above) and address what is needed to move it along. In the companies where this does occur, things are faster, and there is less friction and little dysfunction. Products get released to market faster. Initiatives get launched with ease. The culture is one of empathy and respect. This approach allows all involved to map where we are in any transaction and, to accept, decline, or counter the next exchange accordingly.

What are the outcomes?

- Coordinate action; meetings and projects go faster, easier, and smoother

- Build a cohesive framework for collaboration that can scale

- Cash in on the asset (and mitigate the cost) of each individual’s Personality and Transactional Behavior

- Accelerate initiatives; speed up the time to complete actions, projects, and product or service launches

- Train participants how to produce ethical influence

- Produce large-scale buy-in and compliance for enterprise initiatives

[this] has provided our team with the language and framework to communicate more effectively with each other, hold more efficient and productive meetings, and appreciate the value each person brings to the team. I am feeling more confident in my role and my personality, and I’m feeling more optimistic about reaching our team’s aims.[8]

Marika Meertens, Western Digital Corp

AUTHOR

John Patterson

Co-founder and CEO

INFLUENTIAL U

John Patterson co-founded and manages the faculty and consultants of Influential U global. Since 1987, he has led workshops, programs, and conferences for over 100k people in diverse professions, industries, and cultures. His history includes corporate curriculum design focusing on business ecosystems, influence, leadership, and high-performance training and development.

[1] US National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, THE EVOLUTION OF EUSOCIALITY, pg 1. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3279739/

[2]E.O. Wilson is Honorary Curator in Entomology and University Research Professor Emeritus, Harvard University. E.O. Wilson is generally recognized as one of the several leading biologists in the world. He is acknowledged as the creator of two scientific disciplines (island biogeography and sociobiology), three unifying concepts for science and the humanities jointly (biophilia, biodiversity studies, and consilience), and one major technological advance in the study of global biodiversity (the Encyclopedia of Life). Among more than a hundred awards he has received worldwide are the U. S. National Medal of Science, the Crafoord Prize of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences (considered the equivalent of the Nobel Prize, for ecology), and the International Prize of Biology of Japan. He has received two Pulitzer Prizes in nonfiction (in 1979 for “On Human Nature,” and in 1971 for “The Ants,” which he co-authored with Bert Hölldobler), the Nonino and Serono Prizes of Italy, and the COSMOS prize of Japan.

[3]US National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, THE EVOLUTION OF EUSOCIALITY, pg 1. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3279739/

[4]ibid

[5]ibid

[6]ibid

[7]ibid

[8] testimonial, Marika Meertens, Western Digital Corporation, program: Transactional Competence Across Teams™ 2019